LPS-EB (Standard)

-

Cat.code:

tlrl-eblps

- Documents

ABOUT

Lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli 0111:B4

LPS-EB is a preparation of smooth (s)-form lipopolysaccharide (LPS) purified from the Gram-negative E. coli 0111:B4, a pathogenic serotype of E. coli known to cause significant gastric disease [1, 2]. LPS-EB is a potent activator of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4).

Mode of action

LPS activates the innate immune system through its recognition by TLR4. At the cell surface, activation of TLR4 initiates the MyD88-dependent pathway leading, ultimately to the activation of NF-κB [3]. Also, the TLR4 complex can be endocytosed in a CD14-mediated fashion. This results in TRIF-dependent production of type I IFNs [3].

Two grades of purity:

- LPS-EB is a standard lipopolysaccharide (LPS) preparation extracted by a phenol-water mixture. LPS-EB contains other bacterial components, such as lipoproteins, and therefore stimulates both TLR4 and TLR2.

- LPS-EB Ultrapure is extracted by successive enzymatic hydrolysis steps and purified by the previously described phenol-TEA-DOC extraction protocol [4]. This process removes contaminating lipoproteins, and therefore LPS-EB Ultrapure only activates TLR4.

![]() Learn more about TLR4 and its co-receptors

Learn more about TLR4 and its co-receptors

References:

1. Coleman W.G., Jr. et al., 1977. Genetic analysis of Escherichia coli O111:B4, a strain of medical and biochemical interest. J Bacteriol 130:656-60.

2. Viljanen M.K. et al., 1990. Outbreak of diarrhea due to Escherichia coli O111:B4 in schoolchildren and adults: association of Vi antigen-like reactivity. Lancet 336:831-4.

3. Kuzmich N.N. et al., 2017. TLR4 signaling pathway modulators as potential therapeutics in inflammation and sepsis. Vaccines (Basel) 5(4):34.

4. Hirschfeld M. et al., 2000. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 165(2):618-22.

All products are for internal research use only, and not for human or veterinary use.

SPECIFICATIONS

Specifications

TLR4

10 ng/ml - 10 µg/ml (LPS-EB Standard)

10 EU/ml - 104 EU/ml (LPS-EB Ultrapure)

5 mg/ml in water

TLR4 activation in cellular assays

TLR4 activation

Sepsis research

Each lot is functionally tested and validated using cellular assays.

CONTENTS

Contents

-

Product:LPS-EB (Standard)

-

Cat code:tlrl-eblps

-

Quantity:5 mg

1.5 ml endotoxin-free water

Shipping & Storage

- Shipping method: Room temperature

- -20°C

- Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles

Storage:

Caution:

Details

Types of LPS

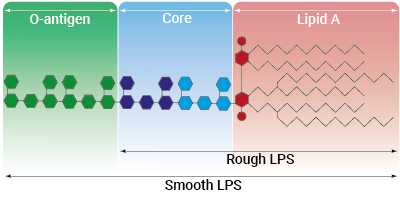

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a major constituent of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. It comprises three covalently linked regions:

- the lipid A (endotoxin)

- the rough core oligosaccharide

- the O-antigenic side chain.

Wild-type LPS contains the O-side chain and is referred to as smooth (sLPS). Some bacterial strains (e.g. Salmonella Typhimurium, Brucella canis) have lost the O-side chain. This mutated form is called rough (rLPS). Both sLPS and rLPS share the same receptor complex (TLR4-MD-2-CD14), but their mechanism of action differs. While CD14 is necessary for sLPS NF-κB and IRF signaling, it is dispensable for rLPS NF-κB signaling. It has been hypothesized that rLPS activates a broader range of cells (CD14 positive, low, and negative), accounting for higher toxicity [1].

Nevertheless, both LPS variations elicit potent innate immune responses. The resulting signaling triggers the release of pro‑inflammatory cytokines, which can lead to both acute and chronic inflammatory diseases. It is all about balance: small controlled amounts of LPS can be protective and large uncontrolled amounts can lead to disastrous outcomes, such as septic shock [2]. Contamination by LPS is a major threat to health, research, and industry, as it can interfere with signaling cascades and cytokine production or induce septic shock in vivo[3]. Thus, its accurate detection, as well as the discrimination between LPS-induced and non-LPS-induced signaling, is crucial to obtain unbiased results and 'sterlie' products. However, despite its highly inflammatory nature, LPS has remarkable therapeutic potential and features many characteristics needed for an effective vaccine adjuvant[4].

Toll-like receptor 4 signaling

The Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) was the first TLR identified and is an important pattern recognition receptor (PRR) in innate immunity and inflammation. It is found both on the cell surface and in endosomes of innate immune cells including monocytes and macrophages, as well as on intestinal epithelium and endothelial cells [5]. TLR4 can recognize pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs). However, it is primarily activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and its toxic moiety Lipid A [6]. TLR4 does not directly interact with LPS but requires essential adaptor proteins [3]. The soluble LPS-binding protein (LBP) extracts monomeric LPS from the microbial membrane and transfers it to CD14 (cluster of differentiation 14). This membrane-bound protein then interacts with MD-2 (myeloid differentiation factor 2), which is constitutively associated with the TLR4 ectodomain. The ligand-loaded MD-2 subsequently binds to another TLR4/MD-2/LPS complex, leading to their dimerization [7]. Interestingly, TLR4 is the only TLR able to trigger two distinct signaling cascades [5]:

- the MyD88-dependent activating NF-κB pathway (at the cell surface)

- the TRIF-dependent activating IRF pathway (in endosomes)

At the cell surface, activation of TLR4 initiates the TIRAP-MyD88-dependent pathway, ultimately leading to the activation of NF-κB and the production of a pro-inflammatory response. Also, the TLR4 complex can be endocytosed into endosomes in a CD14-mediated fashion. This results in the stimulation of IRF3 (interferon regulatory factor), which modulates the expression of type I IFN [3].

TLR4 signaling is crucial in both acute and chronic inflammatory disorders and thus, is an attractive target for novel treatments [5]. Stimulating drugs are useful for the development of vaccine adjuvants or cancer immunotherapeutics, whereas TLR4-inhibition is a therapeutic approach to treat septic shock or autoimmune inflammatory pathologies such as atherosclerosis [8].

References:

1. Zanoni I. et al., 2012. Similarities and differences of innate immune responses elicited by smooth and rough LPS. Immunol Lett. 142(1-2):41-7.

2. Godowski P., 2005. A smooth operator for LPS responses. Nat Immunol 6:544-6.

3. Kuzmich N.N. et al., 2017. TLR4 signaling pathway modulators as potential therapeutics in inflammation and sepsis. Vaccines (Basel) 5(4):34.

4. McAleer J.P. & Vella A.T., 2010. Educating CD4 T cells with vaccine adjuvants: lessons from lipopolysaccharide. Trends Immunol 31:429-35.

5. Ou T. et al. 2018. The pathologic role of Toll-Like Receptor 4 in prostate cancer. Front Immunol 9:1188.

6. Cochet F. et al., 2017. The role of carbohydrates in the lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) signalling. Int J Mol Sci. 18.

7. Tanimura N. et al., 2014. The attenuated inflammation of MPL is due to the lack of CD14-dependent tight dimerization of the TLR4/MD2 complex at the plasma membrane. Int Immunol. 6:307-14.

8. Romerio A. & Peri F., 2020. Increasing the Chemical Variety of Small-Molecule-Based TLR4 Modulators: An Overview. Front Immunol.11:1210.

DOCUMENTS

Documents

Technical Data Sheet

Safety Data Sheet

Validation Data Sheet

Certificate of analysis

Need a CoA ?